Rational Application-Level Threat Modeling

Please make sure you check out the preceding posts in the series:

In order to secure our operations and the underlying systems, we’re moving away from perimeter protection, where the failure of one single control leads to exposure of the entire network, towards separating failure domains into zero trust networks. Failure domains are cohesive areas within an architecture which share a common threat profile, i.e. risks and challenges to architect for.

In order to speak rationally about risks, we’re trying to get to a point where we can complete the following template:

As an ACTOR

I want to OUTCOME

By EXPLOIT

To ASSET

Because MOTIVATION

We’ve established what assets, actors, and disaster scenarios are. In the following paragraphs, we’ll investigate how to map the architecture of a system and use that onformation to discover attacks and develop mitigation strategies.

Privilege & Trust Boundaries

A tool to help structure the defenses of a system is called data flow diagrams, which visualizes the flow of data throughout your system, thereby mapping your architecture in the process. When applying them in a microservices environment, we’ll typically see that our services come together in highly cohesive clusters that are loosely coupled to the outside and share common traits like trust and privilege.

Need to know is about what information a process needs to have access to in order to do its job, i.e. a minimum set of permissions needed to complete a task. This is being done to limit the access to what data is exposed. For example: In an organization not everybody has access to contracts or financial information. As such, a permission is a property of an object, as in a file or a table in a database. It says which classes of agents are permitted to see the object, thus assuming that the user knows what to responsibly do with the data exposed to them, which leads to trust you put into data upon which your system reacts. The presence – or the lack of – this kind of trust is called a trust boundary. When data crosses over a trust boundary, you would put validations and sanity checks in place in order to make sure that what the user does actually makes sense. Instead of littering these kinds of sanity check all over your code, at any later point, you might choose to go garbage-in/garbage-out, since the requests have already been sanity checked at the point of ingress.

Least Privilege on the other hand is about limiting the actions that can be performed with the information discoverable by a process, i.e. having a minimum set of privileges to complete a task. A privilege is a property of an agent, as in allowing an agent do things that are not ordinarily allowed to agents with lower privilege levels. For example, there are privileges which allow a superuser to write to an object or file that a regular user can only read, and privileges which allow a superuser to perform maintenance functions such as restart the computer, which are obviously off limits to others. Think of a system that is connected to the internet: While you would have no problem exposing port 80 (http) and 443 (https) of an application server to the internet, you would not expose any other ports. Additionally, you’d certainly not expose the database, which is accessed by the application server, to the internet. On the contrary, you’d create separate credentials for the application server to read, and to read/write to the database, which the server would choose from, depending on which HTTP endpoint is being invoked. This is called a privilege boundary.

In reality, those two concepts may or may not be clearly distinguishable, which does not make thinking about them any less valuable. In your considerations, you should include processes, data stores, data flows, network layout. In many cases, when you attack one machine, you often see the whole network unfold in front of you. For example, you have a internet-exposed server which connects to a database. Then it makes sense to assume that the server can and will be attacked. Hence the database might get compromised. So the protective measures you put in place should block the database from ever establishing an outbound connection, as there is no good reason for this to happen. In this example we see that these boundaries work both ways. Typical things you do on privilege/trust boundaries is monitoring, logging, load balancing, network segregation, firewalls, sanitization, intrusion detection, rate limiting, using dedicated computing or networking infrastructure, etc.

Threats, Exploits, and Vectors

The final missing piece in disaster scenarios at this point is looking into how it actually comes to pass. In that sense, a threat is what we’re trying to protect against: Anything that can exploit a gap in your protection efforts, and obtain, damage, or destroy an asset, but has not yet materialized. One of the more common ways to classify threats is Microsoft’s STRIDE model (Shostack, 2014), which is used to help in finding and reasoning about things that can go wrong:

- Spoofing of identity: Illegal access from an untrusted source by successfully disguising to be coming from a known source. Popular examples for spoofing include credentials, IP addresses, HTTP headers, or geolocation.

- Tampering: Circumventing validations by changing supplying a system with falified data. Popular examples include cookies, request parameters, or rewriting data in transit.

- Repudiation: Successfully challenging the validity of a contract. Systems generally aim for non-repudiation by collecting access logs and audit trails to be able to correlate a user’s interactions throughout the system. An example would be challenging that a transaction was done by a user, without the operators of the systen being able to prove otherwise, which would result in the transaction being written off as a loss.

- Information disclosure: Illegal exposure of information to individuals who are not supposed to have access to it.

- Denial of service: Making a resource unavailable, e.g. by deletion or removal, using up available computing power, or occupying available network bandwidth.

- Elevation of privilege: A user can illegally gain elevated access to resources that are normally outside of their privileges, thereby allowing unauthorized actions.

When we put all of that together, we understand that risk, is essentially speaking about an event at the intersection of assets, threats, and vulnerabilities. It is important to understand that the threat has not yet materialized into an exploit. That being said, it is still very hard for engineers to think in terms of exploitation, let alone think through a successful attack in order of the attack, which requires an engineer to flip their entire thought process around. However, there is a way to leverage an engineer’s intimate knowledge of the system to discover attack vectors.

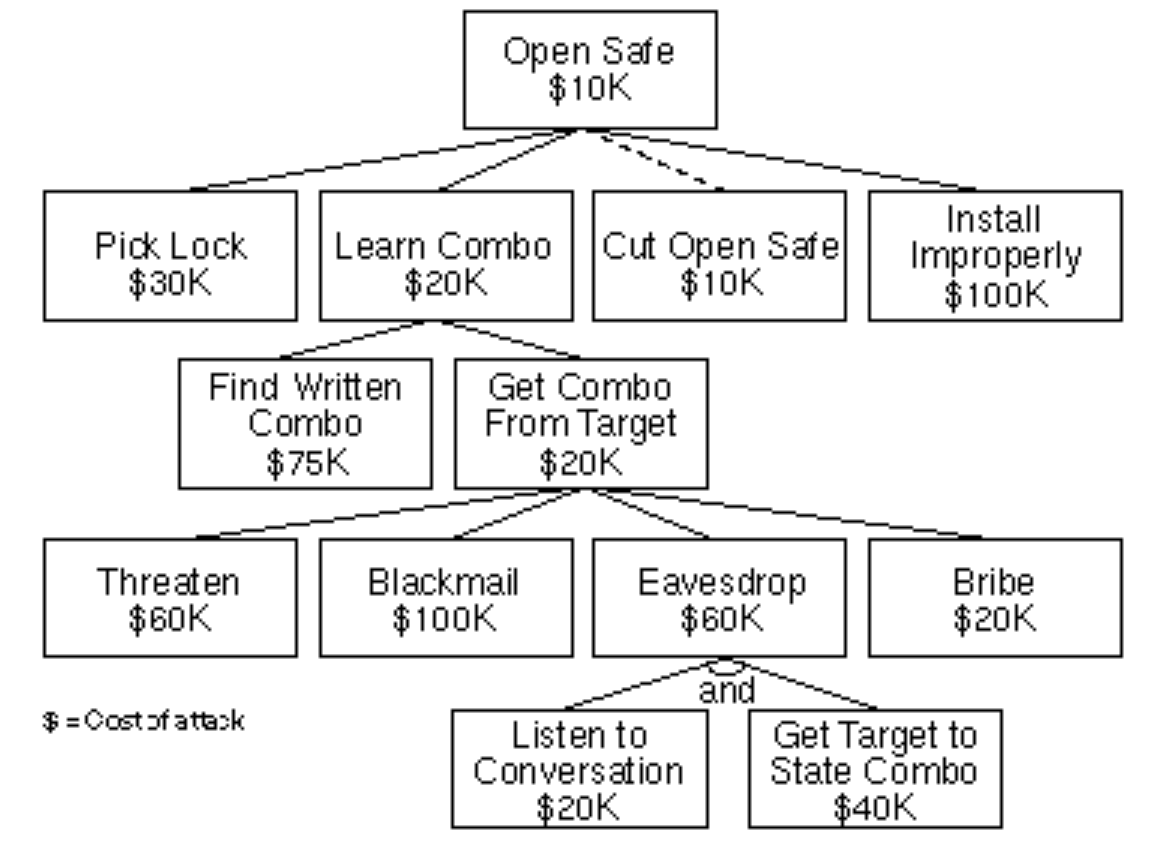

Attack trees are a methodology of analyzing the security of systems that allows for top-down discovery of attack vectors in a tree-like structure. You start by using the outcome of the attack – the disaster scenario, consisting of asset, attacker, and the compromise of at least one of the security goals – as the root node. This ties your security efforts back to the worries that your stackeholders have brought up. The first set up child nodes is a simple enumeration of every place where you can get a hold of the asset w.r.t. the security goal. Once you have done that, you switch from CIA to STRIDE and move towards application-level threat modeling, thinking of the concrete attacks against each hop. Then you rinse and repeat, traversing the tree breadth-first, harnessing the entire engineering knowledge in the teams’ heads to model weaknesses of your systems. Every single path from root to leaf node is called an attack vector, consisting of a full-scale attack on your system leading to the outcome you and your stakeholders are afraid of. This allows us to think about defenses: An attack can be thwarted at every step in the process, which is the reason why it’s called defense in depth. The resulting tree shows the relation between the different defenses and gives a full picture of both defense-in-depth and the countermeasures. Here’s an example for a simple attack tree against a physical safe (Schneier, 1999):

A frequent observation is that areas people think of as vulnerable usually aren’t, since there was already plenty of thinking going into these specific parts of the system. Another observation is that team members often make assumtions about the security and stability of other areas of the system, leading to surprise when these issues are surfacing during the creation of an attack tree.

Risks and Countermeasures

Now that we’ve broken our high-level threat model down to the application level and understoof how one of these attacks actually might come to pass, we need to ask ourselves: How much can I stand to do about it? It ties the delivery and assurance work within the team back to the management-layer of your organization involved in the high-level threat modeling. Any response (or the absence of it) needs to be seen in context of the business our products are supporting, having an impact on personnel, profitability, market capitalization, any many more. Hence, the decision on countermeasures is not taken in isolation within the product team, but needs to be in agreement with the business side of your organization. The four typical courses of action are

- Accept: You have identified it and logged it in your risk management software, you take no action. Please note that this is independent from inaction in the sense that acceptance is the result of an informed decision rather than ignorance.

- Avoid: Change your plans to avoid the risk.

- Transfer: Transfer the impact and management of the risk to someone else. For example: Instead of hosting your own data center and be responsible for every aspect of it, you use cloud providers.

- Mitigate: Limit the impact of a risk and/or reduce its likelihood.

When confronted with a vulnerability, a common knee-jerk reaction for an engineer is to try and mitigate where possible. But that is not always necessary, as all of the above strategies are equally valid, depending on the context. A good threat model makes that context clear:

The next knee-jerk reaction is to always go for the risk, which proves to be hard sometimes. Please note that it is equally valid to mitigate risk as it is to mitigate the outcome. For example, the devops movement has brought an end to many of the most dearly-held assumptions of sysadmins optimizing for uptime. Instead, the devops movement advocates for treating servers like cattle, not pets. If one goes down, it gets replaced rather than repaired (Bias, 2016):

Arrays of more than two servers, that are built using automated tools, and are designed for failure, where no one, two, or even three servers are irreplaceable.

Another analogy can be made for XSS and the way React handled it. The DOM is still as vulnerable as it always was, but since React ditched the DOM for parsing and instead build a DOM itself, it can work around the DOM’s weaknesses. The risk is still there, but the impact is 99% mitigated as long as you stay within React’s realm.

Bringing security into your organization

Now that we’ve taken a look at how we can tie our security efforts back to the security goals, the next step is to get the organization to sign off on our efforts. However, there are some caveats. We need to communicate the following points:

- Why is security thinking important?

- What is the impact of built-in security?

- When is the right time to start security thinking?

- How do I get my point across?

Let’s first investigate how unaddressed security manifests itself in a software development life-cycle. We typically see it surfacing like technical debt, which means your development starts to slow and gets bogged down in workarounds, and typically ends up being a full-blown delivery risk showing up in red on your status reports. The good thing is, we’ve learned how to handle technical debt.

Let’s start with a Project Manager’s perspective. We shall not fall for the illusion that we can probably sneak our security work in under the radar. This is not one of those topics. Security thinking …

- will change your stakeholders: More likely than not, there are people in your organization that are already handling some of the issues you’re facing. Amongst others, there is likely a legal team that you want to get in touch with when you’re handling commercial data or user data to whom you want to have a communication channel to understand how to handle this data safely, and who know what to do in case something goes sideways. There will be an infrastructure team to whom you want to speak about your security requirements, e.g. network segregation, provisioning of machines, dedicated infrastructure, etc.

- has development cost: You will see an increase in marginal cost, which will likely subside over time, but can’t be ignored. All of the things I’ve mentioned before require time to be worked upon, and we haven’t even begun implementation of security measures at this point.

- impacts your team structure: Taking it seriously, you will need to call upon senior team members with a background in security. You might also have to bring in people in an advisory capacity for upskilling junior team members. On top of that, security experts and penetration testers are costly, but there’s no way around bringing them in.

- impacts your product delivery: You will likely have to rethink deadlines, as you will need to work around catering to the new responsibilities. This might involve bringing in experts from these teams into your delivery team, so that their expertise can be addressed continuously.

Let’s shift to a Product Owner’s perspective, where you will find yourself involved in reasoning about the disaster scenarios and their impact. This includes financial loss, reputational damage, missed opportunities, and can range all the way up to bodily harm or loss of life.

As a Quality Analyst, you will find yourself thinking about a whole new set of cross-functional requirements, and how they need to be addressed to provide a consistent view on the quality of the product, e.g. in the testing strategy of the product. This may mean you will have to interact with security researchers and penetration testers and pen test reports.

As a dev, you will have to find ways to upskill and find your way around in a world initially full of unknown unknowns, in order to keep up the maintainability of your product. This involves managing complexity of security requirements, learning from mishaps, and making those trade-offs during development.

Where do I start security thinking?

Starting at the beginning of product development is obviously the easiest way to get the ball rolling. If you have the luxury of building a product from scratch, one of the ways this is done is a multi-day or multi-week requirements gathering phase – aka Inception – where all of the stakeholders are present in the same room (Caroli, 2017).

However, that is unlikely to be an option in most cases, as you’ll be joining projects mid-flight. But do not despair as there are many things you can do to catch up. The first step is to engage with stakeholders (business, IT security, legal, government etc) and make them aware of your security requirements and where they come from. The second step is to create abuser personae, abuse cases, and threat models, thereby creating awareness. The third step is to build security incrementally with each user story, as security thinking is a culture that needs to be grown inside a team. Awareness is a good starting point, but it only gets you so far, from which point onwards you continue to build security story-by-story, revisit on architectural changes, product direction, new use cases, new threats, architectural refactorings, etc.

What if my organization is not listening?

Security in general is an abstract and highly technical topic, which is why tieing it back to the “real world” becomes so much more important.Having reasonable threat models should go without saying. Imagine speaking to your organization’s management board using terms like “port scanning”, “file inclusion”, and “buffer overflow”, which will be a pretty short conversation and you won’t be invited again. The first step is to use the outcomes from high-level threat modeling to communicate the commercial, reputation, and business impact of security breach, lay out the alternatives and be open about the implications. Security does not have to be “all or nothing”. Imagine the CIO telling you that a database backup is no priority since the data is not business critical and/or can be reimported from other systems.uChances are he’s probably right about that.

A common theme in modern software development is that cost can be driven down by automation. Test automation, CI/CD, infrastructure-as-code, software-defined networks, and many other things can attest to that. The same is true for security, but be aware that this automation needs to be built first. Creating reusable toolsets and frameworks for your organisation and sharing them with the other teams helps in that regard.

Closing words

References

Bias, The History of Pets vs Cattle and How to Use the Analogy Properly

Caroli, Lean Inception, 2017

Gallagher, How I learned to stop worrying (mostly) and love my threat model, 2017

Schneier, Attack Trees, 1999

Shostack, Threat Modeling: Designing for Security, 2014

Other resources

Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP)